Maurice Crosland, "Popular science and the arts : challenges to cultural authority in France under the Second Empire:" (1)

Jules Verne and the Creation of Science Fiction

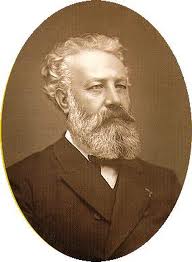

It might be claimed of Jules Verne (1828–1903) that it was he more than anyone else who brought together science and literature. The term ‘ literature ’ is used here in its widest sense. Many of the dozens of stories churned out by Verne under contract would hardly be classified in the same category as some of the masterpieces of Balzac, but whereas the latter could have reasonably expected to be elected to the Académie française, Verne himself realized that his constant outpouring of tales of adventure to satisfy his publisher would never qualify for consideration by that august body.

In some ways Verne could be regarded as a popularizer of science, although that was never his principal intention. He was interested in telling stories in which science, technology and adventure were prominent. As a young man Verne had been directed

Jules Verne

towards the profession of law but he preferred literature. A crucial event in his life was his introduction in 1850 to Jacques Arago, the explorer and brother of the prominent scientist François. Jacques Arago ’s house was a meeting place for scientists and travellers. The conversation there stimulated Verne to become seriously interested in science. Other influences included the writings of Edgar Allan Poe, who opened a new chapter in literature by his treatment of the fantastic. It is significant that Verne should later have commented that he would have had a higher opinion of Poe if he had ‘respected a few elementary laws of physics ’. Verne’s particular genius was to incorporate fact skilfully into a narrative and to marry fact with fiction. The facts were usually geographical, scientific or technological. Part of his success lay in his recognition that most readers wanted to be amused rather than educated. Any teaching was, therefore, incidental. In some of his stories there is a fair input of popular science. Thus in Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea he provides a long list of authorities on many branches of science. He also goes into considerable detail in the classification of shells, molluscs and fish. Verne was successful in presenting the possibilities of science in a romantic light. In many stories he presented real scientific possibilities of the future.

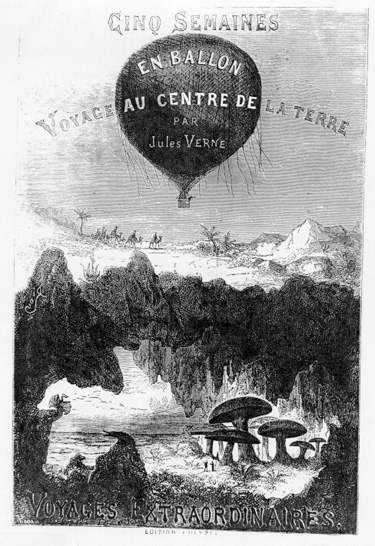

Like many of the professional popularizers of science, Verne’s stories were often first published in magazines or newspapers. Thus his early book Un Voyage en ballon [A Voyage by Balloon] was first published in the periodical Musée des familles (1851) under the heading ‘ Science for the family ’. His later book De la Terre a la lune [From Earth to the Moon] appeared first in the Journal des débats in 1865. Verne ’s friend and publisher Herzel saw his writings as part of an increasing popular interest in science. He wrote as follows in his preface to Verne ’s Voyages et aventures du Capitaine Hatteras (1866) :

Like many of the professional popularizers of science, Verne’s stories were often first published in magazines or newspapers. Thus his early book Un Voyage en ballon [A Voyage by Balloon] was first published in the periodical Musée des familles (1851) under the heading ‘ Science for the family ’. His later book De la Terre a la lune [From Earth to the Moon] appeared first in the Journal des débats in 1865. Verne ’s friend and publisher Herzel saw his writings as part of an increasing popular interest in science. He wrote as follows in his preface to Verne ’s Voyages et aventures du Capitaine Hatteras (1866) :

The novels of M. Jules Verne have just come at the right time. When an eager public can be seen flocking to attend lectures given at a thousand different places in France, and when our newspapers carry reports of the Académie des sciences alongside articles dealing with the arts and the theatre, it is surely time for us to realise that … the day has come when science must take its rightful place in literature …

Verne shared with the popularizers the idea that science could be applied to human progress, although he maintained a certain scepticism about making too much of the powers of the scientist. . . .

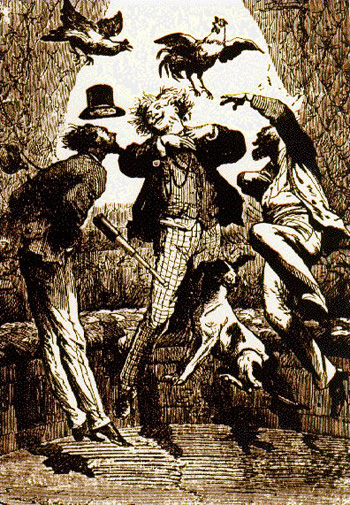

It would be a mistake to think of science fiction as primarily of interest to  scientists; on the contrary, Verne’s novels were read by a wide public. Some were even set to music. In his operettas the irrepressible Jacques Offenbach satirized the world of the Second Empire. Through his music he produces a revolution in popular taste. His Orpheus in the Underworld had taken Paris by storm and he saw distinct possibilities in the work of Jules Verne. He accordingly transformed Verne’s De la Terre a la lune (1865) into an opera,entitled Voyage dans la lune, in which one scene was set in the Paris Observatory. A later opera by Offenbach was Le Docteur Ox (1877), based on Verne’s novel of that name, which fantasized on the effects a new doctor created on the population of a sleepy provincial town by administering large doses of oxygen. Thus science not only overlapped with the world of literature but also that of music.

scientists; on the contrary, Verne’s novels were read by a wide public. Some were even set to music. In his operettas the irrepressible Jacques Offenbach satirized the world of the Second Empire. Through his music he produces a revolution in popular taste. His Orpheus in the Underworld had taken Paris by storm and he saw distinct possibilities in the work of Jules Verne. He accordingly transformed Verne’s De la Terre a la lune (1865) into an opera,entitled Voyage dans la lune, in which one scene was set in the Paris Observatory. A later opera by Offenbach was Le Docteur Ox (1877), based on Verne’s novel of that name, which fantasized on the effects a new doctor created on the population of a sleepy provincial town by administering large doses of oxygen. Thus science not only overlapped with the world of literature but also that of music.